Is a wooden house a good example of sustainable construction, if most of the wood comes from 3000km away?

Is a building with a green roof automatically a low-carbon construction?

Is a concrete tower with some vegetation on the balconies a sustainable building?

One significant issue in the world of green and sustainable architecture arises when architects and/ or developers apply the green colour to their promotional drawings, add a few solar panels or a green roof, some eco-friendly words to their descriptions and then label it a sustainable building. We have to call it what it is (most of the time): a fraud.

In the architecture and construction industry, certain words, the use of the colour green and the addition of some vegetation have emerged as symbols of sustainability. However, the connection between these elements and environmental responsibility can be deceptive, reflecting a misleading trend that we know as greenwashing. But we could also call it a green disguise, meaning that what we see is not what we get.

This practice exploits the public’s natural tendency to associate certain symbols, such as green, with environmental friendliness, even when the reality is FAR from true sustainability.

This colour has come to signify a commitment to preserving our planet for future generations, making it an attractive choice for companies that want to portray themselves, or their products/ services, as environmentally conscious.

However, it’s important to claim that these isolated elements alone do not guarantee the eco-friendliness of a building.

In many (many, many…) cases, the inclusion of ‘green’ elements or systems seems to compensate for what the design itself failed to establish as the project’s core essence.

True sustainability in architecture and construction involves (among other topics):

- thoughtful planning and design (from day one), even considering the possibility of using/ transforming existing structures, rather than starting from scratch or demolishing, as proclaimed by the grandiose Lacaton & Vassal;

“It’s about considering the existing as a resource and as a value – and not about always seeing it as unsatisfactory and too constraining.” Anne Lacaton

- responsible choice of ALL the materials and construction systems, including, for example, local sourcing (choosing locally sourced materials that help reduce transportation-related environmental impacts and supports local economies);

- energy efficiency (passive and/ or active, during all its life cycle);

- waste reduction (planning, efficiency, prefabrication…);

- social responsibility (true sustainability goes beyond environmental considerations, including the well-being of occupants or social equity, for example);

- the long-term durability of structures and materials (hypothesis: is an ecological material that lasts 2 years more eco-friendly than a carbon-heavy material that lasts 100 years or more?);

as well as defining the way in which the building will be demolished or, better still, deconstructed or disassembled (adaptability and flexibility), allowing its parts to be used in another construction and preventing materials from being downcycled or sent to landfills.

(shouldn’t all new buildings be able to be disassembled like Lego and the parts used in further constructions?)

But why do people (still) fall for greenwashing tactics in the architecture and construction industry?

The answer lies in a lack of knowledge, of critical thinking, and some (conscious/ voluntary) ingenuity.

To combat greenwashing, both consumers and industry professionals must develop critical thinking and demand more information from architects, engineers, contractors and material suppliers. Trusting sustainability certifications, which evaluate buildings on a wide range of criteria, ensures that sustainability is measured holistically.

With so much knowledge and information at our disposal, it’s a shame to be fooled by amateurish strategies that damage our built environment and personal life.

The color green, once a symbol of eco-friendliness, risks becoming a marketing bait, persuading the public with works that fall short of true sustainability.

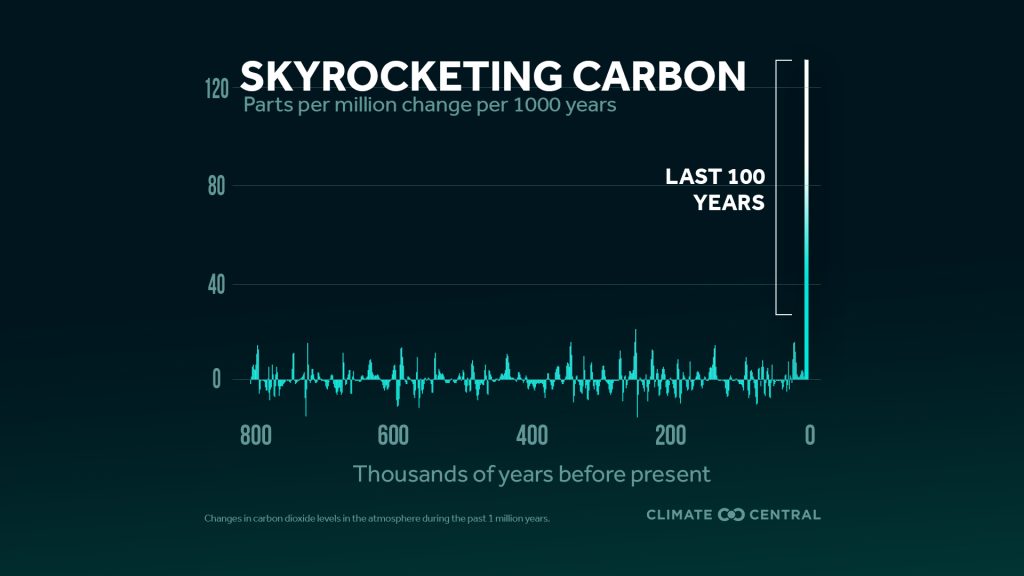

“Buildings are currently responsible for 39% of global energy related carbon emissions: 28% from operational emissions, from energy needed to heat, cool and power them, and the remaining 11% from materials and construction.

Towards the middle of the century, as the world’s population approaches 10 billion, the global building stock is expected to double in size. Carbon emissions released before the built asset is used, what is referred to as ‘upfront carbon’, will be responsible for half of the entire carbon footprint of new construction between now and 2050, threatening to consume a large part of our remaining carbon budget.” via World Green Building Council

Architecture is about problem-solving and meeting specific needs.

In many cases revolves around understanding the context and integrating with existing conditions in a beautiful and harmonious way.

It’s about creating spaces that, not only serve a specific purpose, but also enhance the overall experience, fostering a balance between functionality, comfort and aesthetics.

Today, it’s also about the need of using the scientific data we have at our disposition at this time to build and leave a positive legacy.

As I wrote when describing POC Régua, built from two used shipping containers, “having to diminish the quantity of resources that we extract from the soil, it’s mandatory that new buildings start to use more and more existing materials and structures.”

We, clients, we/ I, architect(s), have to change the way we demand, prescribe, plan, design, question. We have to be tough. Rigorous. Strict.

Green has to come from inside.

Green has to become the starting point.

Although the effort is large and we, architects, are designing the path as we walk it, we should aspire to be the change we wish to see.

Disclaimer: The images displayed do not depict works or projects that claim to be sustainable.

PS: Please share your thoughts, questions or experiences.